|

By Bryan E. Robinson, Ph.D. When it comes to your inner critic, my advice is to not take advice from someone who doesn’t like you. That’s like returning to the perpetrator for healing after you’ve been abused. —Patrick Califia, writer

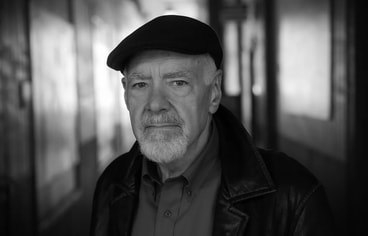

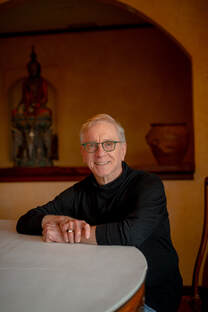

Do you hear voices in your head? Of course you do if you’re a writer. Creative people have one relentless voice, in particular, that lives in our heads and never rests—an inner critic that puts us under the microscope, bludgeons us with criticism, and tells us how worthless, selfish, dumb, or inept we are. That kick-butt voice pops up like burnt toast with such lightning speed we don’t even notice, eviscerating us with name-calling, discouragement, and putdowns. The critical voice tells you that you can’t; you should, ought to, have to, or must. It knows where you live and where to find you. And it does. When you’re working on an important deadline, it stalks you to your desk and whispers over your shoulder as you pen a manuscript. It could be scolding you right now. Listen closely. Do you hear it: “No, that’s not right! You don’t know what you’re doing! You might as well give up! Who do you think you are? You’re an imposter.” Burnt toast anyone? The critical voice in our head isn’t who we are. It’s a part of us, not all of us. It’s the lowercase “self.” Who are we, then? We are the captain of our ship—not a passenger, the coach of our team—not a player, the conductor of our symphony—not a musician, the CEO of our boardroom—not a stakeholder. We’re the true writer’s Self with a capital “S”—the writer who hears and sees the lowercase “self” or critic. There’s no use fighting, debating, or arguing with your inner critic. It always has a comeback and always wins, plus you can’t get rid of it. The key is to watch it and let it come and go without personalizing it. When we oppose or try to reason with the Critic, we give it credence and, instead of streaming on through, it takes up residence. Studies show when the critic comes down hard on ourselves after a mistake or failure, it reduces our creativity and chances of writing success. When you think about it, eviscerating ourselves after a letdown is like fighting the fire department when our house is on fire. It’s just as easy to affirm ourselves with positive messages as it is to tear ourselves down with negative ones. The best way to address the inner critic when it pops up is to observe it like you would inspect a blemish on your hand instead of reacting to it. Listen to it with a dispassionate ear as a part of you. Imagine someone scolding you over your cell phone and you hold the phone away from your ear. In the same way, you can listen to the Critic’s message from afar as a separate part from you, not all of you. In addition to hearing it as a part of you, not you, a dispassionate ear gives you distance from the Critic’s voice and keeps you from attacking yourself. Plus, it keeps you from believing the voice’s made-up story. If you’re stuck with your writing, try replacing criticism with Self-compassion (from the capital Self) each step of the way. Self-compassion is a powerful resilient tool that stands up to harm and is more likely to lead to heights of literary success. So put down your gavel and amp up your kinder, compassionate side. In times of writing struggles, give yourself pep talks, positive affirmations, and talk yourself off the ledge instead of letting your Critic encourage you to jump. Vincent Van Gogh once said, “If you hear a voice within you say, ‘You cannot paint,’ then by all means paint, and that voice will be silenced.” Bryan Robinson says, “If you hear a voice within you say, “You cannot write,” then by all means write, and that voice will be silenced.” Bryan E. Robinson is a licensed psychotherapist and author of 40 nonfiction books. He is also author of two murder mysteries—both soon to come from Level Best Books: Way DEAD Upon the Suwannee River and She’ll Be KILLING Round the Mountain. His tagline is, “I heal by day and kill by night.” He is also author of Daily Writing Resilience: 365 Meditations & Inspirations for Writers. His website is www.bryanrobinsonphd.com.

1 Comment

by Erica Miner As a writer, I am not a pantser; quite the opposite, in fact. My writing methodology reflects my approach to honing my craft in my former life as a musician. In practicing music, whether as a soloist or as a violinist in the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra in New York, planning was always key. This remains true in my writing life as well.

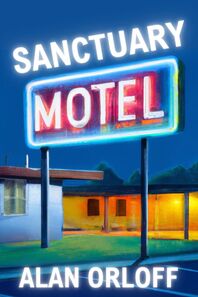

Writing a novel is much like practicing a concerto or a Wagner opera. Both require a slavish devotion to perfection, with one important distinction. In a concerto, you’re perfecting a piece written by someone else. With a novel, you’re creating your own personal material, and starting with a blank slate. That means meticulous planning. And it all starts with an outline. In a mystery novel, plotting is more complicated than in other genres. Like a jigsaw puzzle, if one piece doesn’t fit exactly, the entire plot is in danger of falling apart. In addition, two important elements must be determined before you can start writing this type of story: the ending, and the identity of the villain or perp. I also think in terms of starting with the ending and working my way backwards to make sure each plot point fits logically with what came before it. When I write my outline, the broad strokes come first: seven or so large beats, the bones of the story. Then I start to expand the beats into detailed plot points. Eventually, I create an in-depth beat sheet of each scene in the book, from beginning to end, making sure to include the characters’ emotional arcs and interactions and relationships with each other as part of every beat. Once I have a rough draft of my outline, I dissect my plot as I do my music, slowly examining every word as I do every note as if under a magnifying class. Without an outline, this would be impossible to accomplish. Writing an outline is very labor intensive, but the rewards are great. It’s a wonderful feeling when I finally allow myself to use this blueprint to write the actual novel. Plus, I have the outline to refer to during the process, adding or deleting, changing, and refining as I go along. Is it any wonder that I outline meticulously? Former Metropolitan Opera violinist Erica Miner is an award-wining author, screenwriter, arts journalist, and lecturer. Her debut novel, Travels with my Lovers, won the Fiction Prize in the Direct from the Author Book Awards, and her screenplays have won awards in the WinFemme, Santa Fe and Writers Digest competitions. Based in the Pacific Northwest, Erica continues to balance her reviews and interviews of real-world musical artists with her fanciful plot fabrications that reveal the dark side of the fascinating world of opera. Aria for Murder, published by Level Best in Oct. 2022, is the first in her Julia Kogan Opera Mystery series. Prelude to Murder, the sequel set at the Sante Fe Opera, was released September 2023. Book three,taking place at the San Francisco Opera is due for release in 2024. https://www.ericaminer.com By Alan Orloff  If you asked 50 writers to describe their “writing processes,” you’d probably get 75 different responses. Some writers stick to a set of inviolable rules, others “meander across the meadow,” while others invoke voodoo dolls and incense, heavy on the incense (substitute “alcohol” for “incense” as required). Hey, whatever works! Here are a few questions to help you “define” your writing process, along with my responses. Are you an outliner or a “seat-of-the-pantser”? I’m an outliner. Maybe it’s my quantitative background and schooling (yes, I’m a reformed engineer), but I feel more comfortable when I know where I’m headed. I think if I tried to wing it, I’d write myself into a dark alley in Newark with no visible path home. (No offense to anyone living in Newark! Or in dark alleys!) When I taught writing workshops and my outliners’ outlines weren’t working, I’d suggest they change their outlines. When things weren’t flowing for my pantsers, I’d suggest they change their pants. Ba da bing! Do you write daily or whenever you can grab a chance? Sometimes I write daily, sometimes I write whenever I can grab a moment. (I know, I know—this is a waffle-y answer. Everything’s not always black and white. Or even gray.) When I’m working on a draft, I’m pretty diligent about writing daily. But between projects, I have to admit I don’t write every day. Of course, if you counted emails and social media posts and bios and those frustrating attempts to distill 80,000 words of a novel into four pithy sentences for back cover copy, then I suppose I do write every day. But that’s not the type of writing I call writing. Do you revise as you go or do you plow through? I’m a big proponent of the Plow-Thru Method (patent pending). When I’m in first draft mode, my only goal is to hit my word quota (see below), quality be damned. That’s what the second draft is for—making my first draft readable. And the third draft is for making the second draft not suck, and the fourth draft is for…well, you get the idea. Do you have a daily quota or do you write for as long as the spirit moves you? Per the Plow-Thru Method, I sit at my computer and type until I hit my daily quota. Sometimes it’s a thousand words, sometimes twelve-fifty, and when I’m really behind, two thousand. Depends on the schedule. After I hit my quota, I move on to other things, even if I’m in the middle of a sentence when I hit my mark. Seriously, I am not joking about getting up right in the middle of Do you write what you want or what you think has a shot of selling? Yes. Do you listen to music when you write? I love music. But I can’t write when it’s on. Same goes for talk radio or TV or the latest episode of Bosch. Alan Orloff has published ten novels and more than forty-five short stories. His work has won an Anthony, an Agatha, a Derringer, and two ITW Thriller Awards. His latest novel is SANCTUARY MOTEL, from Level Best Books. He loves cake and arugula, but not together. Never together. He lives and writes in South Florida, where the examples of hijinks are endless. www.alanorloff.com By Leah Dobrinska The single most common question I get asked as a young(ish!) stay-at-home mom of five kids (by day!) and author (by night!) is “how do you find time to write?”

For me, this is like someone asking, “how do you find time to eat?” or “how do you find time to sleep?” Writing is such a crucial facet of my identity and it brings me so much joy that to not do it feels like it would be a great loss to who I am as a person. I often tell people I feel most like myself when I’m writing. But I’ve realized this isn’t exactly what folks really want to know when they ask me this question. They want practical, logistical answers explaining how I find the time to write. Or more accurately, I should say, how I make the time to write, given the other demands on my time. So, I’ve started compiling a list of tips for fellow creatives. I thought I’d share it here. These are things that work for me as a writer who, from the outside looking in, doesn’t have a ton of spare time to devote to my craft. Maybe these ideas will help you make some time to do the thing that fills your cup, brings you joy, and allows you to feel most like yourself.

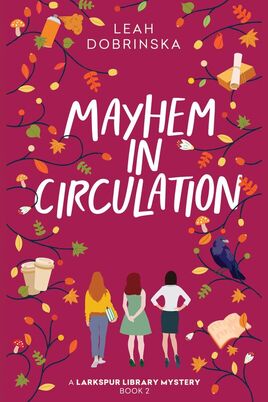

That’s about it. Nothing fancy. Nothing ground-breaking. But this method works for me. As someone who is not a full-time author but instead writes within the margins of her day, these are my tips for other busy creatives. I’d love to hear from you. How do you find time to write? Do we use any of the same strategies? Share your best creative tips in the comments below. Write on! Leah Dobrinska is the author of the Larkspur Library Mysteries, a cozy mystery series set in the Wisconsin Northwoods; the Mapleton novels, a series of award-winning standalone small town romances; and the Fall In Love closed-door romcoms. She earned her degree in English Literature from UW-Madison where she was awarded the Dean’s Prize and served as a Writing Fellow. She has since worked as a freelance writer, editor, and content marketer. As a kid, she hoped to grow up to be either Nancy Drew or Elizabeth Bennet. Now, she fulfills that dream by writing mysteries and love stories. A sucker for a good sentence, a happy ending, and the smell of books—both old and new—Leah lives out her very own happily ever after in a small Wisconsin town with her husband and their gaggle of kids. When she's not writing, handing out snacks, or visiting the local library, Leah enjoys reading and running. Find out more about Leah, join her newsletter community, and connect with her through her website, leahdobrinska.com. Writing a novel is like a car trip with a whiney inner child demanding, “When are we going to get there?” For me, the beginnings are easy. The trip is planned, the car is packed and the excitement about a new experience is growing. My planning usually involves a lot of “think time” imagining the story in my head. After I have the concept, I write a synopsis long-hand to give me a sense of where the story is going. Now I’m set.

Except, like a journey to places unknown, often the road isn’t quite clear. For years I’ve struggled with the middle part of the book. Tina de Bellegarde, a Level Best author, put it so well in a recent podcast when she called it “the messy middle.” It’s those chapters that drive the reader to the climax of the story. They need to be vivid enough to keep the reader drawn in and have the details and clues to make the story real. For me, a good middle is like the difference between traveling for miles and miles over flat, boring prairie, or driving the curving highway through the mountains. One will put you to sleep and the other will keep you anticipating the next bend in the road. Recently, I’ve been stuck in the middle. The first chapters of the newest Cabin by the Lake mystery moved quickly. I had my death (was it an accident or was it murder?), my main character pursuing it and the momentum growing. Somewhere mid-manuscript, my writing car drove straight into the ditch and got stuck in the mud. It felt like I was trying to move the story in one direction and the story itself wanted to go somewhere else—somewhere way too complicated for my writing skills. How to get unstuck? In my case, the first thing I did was try writing through it. I kept on the same track with scenes I’d conceived at the beginning of the book. After several days of getting myself mired deeper and deeper into a place that whiney little voice in my head didn’t want to go, I stopped and let it sit. I worked on revising a short story instead. Next, I sat down with my original written synopsis and wrote out a new one. By this time, the story had changed and new characters had popped in. I needed to decide to keep the changes and the new characters or stick to the old road map. With a new synopsis and a better sense of where the story might go, I deleted the most recent chapters. Oh, I admit, it was painful but necessary. Didn’t someone once talk about the need to kill your darlings? Well, I sent them off a cliff. Was I renewed? Was the car out of the ditch and on its way again, the kid in the back happily occupied with the new landscape? Not exactly. The story still felt flat and a little lifeless. As I told my husband on one of our daily walks, “It’s blah, blah, blah. I’m bored with it.” Perhaps the admission out loud to someone else was the key for me. When we returned from our walk, I realized I needed action to get it going again. I wrote several chapters that included another murder, a wildfire and a daring rescue. The kid in the backseat cheered me on. I’ve reconciled myself that on writing journeys, the middle will often be messy. Here are a few lessons I’ve learned:

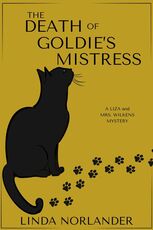

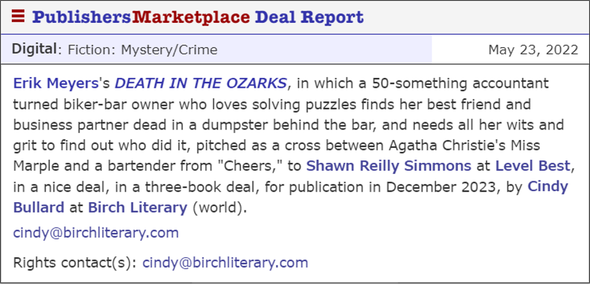

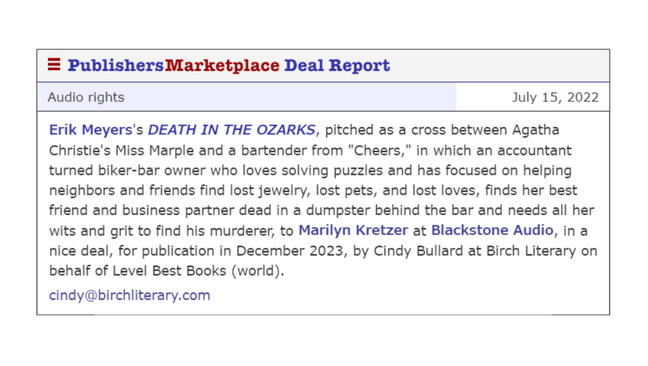

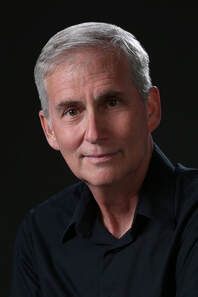

Despite my best efforts, I know the car might still go in circles, get lost or hit the ditch once again. Fortunately, as a mystery writer I can always add another body, another cliff or maybe a wildfire to get it back on the road. Linda Norlander is the author of A Cabin by the Lake mystery series set in Northern Minnesota. Books in the series include Death of an Editor, Death of a Starling, Death of a Snow Ghost, and Death of a Fox. Norlander has published award-winning short stories, op-ed pieces, and short humor featured in regional and national publications. Before taking up the pen to write murder mysteries, she worked in public health and end-of-life care. Norlander resides in Tacoma, Washington, with her spouse. By Skye Alexander Writers, especially beginners, are often advised to “write what you know.” Everyone has a story to tell––maybe two or ten––and for many people, writing a book isn’t quite so daunting if you can draw on the huge body of knowledge and experience you already possess. Although that’s good advice, I find it much more interesting to write about what I don’t know. In the process of researching my books, I dig up a wealth of unexpected booty that fills my stories with riches I never imagined.

I write traditional, historical mysteries in the Agatha Christie vein, set in the mid-1920s. I confess, I never liked history when I studied it in school because most of it centered on rulers, wars, and politics rather than the lives of ordinary people. But once I started researching this colorful period for my Lizzie Crane mystery series I got hooked. I realized how much I didn’t know, and I was determined to rectify that deficit. For example, while doing research for my second novel What the Walls Know, I discovered that the first automatic gate was invented by an Egyptian guy named Heron about 2,000 years ago. He also invented a coin-operated dispenser for holy water. How cool is that? I also learned that some of the world’s great pipe organs have more than 30,000 pipes and seven keyboards, and this incredibly intricate instrument dates back to ancient Greece. Because the book features a cast of mediums and other occultists, I also delved into the Spiritualist movement at the early part of the 20th century––séances, Ouija boards, tarot cards, etc.–which turned out to be fascinating. For my third, recently released book The Goddess of Shipwrecked Sailors set in 1925 in Salem, Massachusetts, I had to bone up on the clipper ship trade between New England and the Orient. In the process, I found out that these beautiful sailing vessels not only brought precious tea, spices, teak, ivory, and silk to the U.S. in the mid-1800s, but also opium (which was legal at the time). The Chinese goddess Quan Yin, sometimes considered the Buddha’s feminine counterpart, is said to have protected seafarers and ferried shipwrecked sailors to shore––hence the title for my book. Many of the ship owners whose clippers made it home safely didn’t want to pay taxes on the valuable goods they’d risked bringing from halfway around the world, so they slipped them past the revenuers via a series of smuggling tunnels built beneath the city of Salem by the country’s first National Guard unit. Because my series is set in the Roaring Twenties and my protagonist, Lizzie Crane, is a jazz singer from New York City, I had to familiarize myself with the jazz musicians of the period. Before I began writing this series, I wasn’t a big fan of jazz but that’s changed as a result of hearing the greats such as George and Ira Gershwin, Bix Beiderbecke, and Louis Armstrong play. YouTube is a valuable resource for this. If you’ve never listened to “Davenport Blues” or “Rhapsody in Blue” I urge you to do so. For my fifth book in the series, When the Blues Come Calling (not yet published), I learned about the rapidly developing music recording industry, how records were made in 1926, and even a portable record player called a Mikiphone that could spin a 10-inch disc yet folded up small enough to fit into a good-sized purse. For me, every day is an exploration into worlds unknown. During my journey, I’ve learned about jigsaw puzzles, merry-go-rounds, rose windows, ladies’ undergarments, Jell-O, New York’s subways, voodoo veves, and so much more. I never know what tidbits of trivia or historic fact I’ll stumble upon and how they’ll influence the direction of my stories. It’s so much more fun that simply recapping what I already know. Skye Alexander is the author of more than forty fiction and nonfiction books. Her stories have been published in anthologies internationally and her work has been translated into more than a dozen languages. In 2003, she cofounded Level Best Books with fellow authors Kate Flora and Susan Oleksiw. The Goddess of Shipwrecked Sailors is the third in her Lizzie Crane mystery series. Skye is also an astrologer and tarot reader, and has trained as a medium. She’s best known for her many metaphysical books including Magickal Astrology and The Modern Witchcraft Book of Tarot. by Heather Weidner  What’s your writing process? This is what works for me. If something resonates with you, give it a try. If it doesn’t work with your schedule and lifestyle, stop and try something else. With this method, I can usually write three mysteries a year. My first novel took five years to write and another two to get published. I edited each little paragraph and chapter, and I did hundreds of rewrites. The revision focus was good, but I never got around to finishing the book. I also read every writing book I could get my hands on. I finally picked the ones that spoke to me and donated the rest of them to the Friends of the Library. It was time for BICFOK. I learned this from the amazing Alan Orloff. BICFOK is butt in chair, fingers on keyboard. Tune out the distractions and write. Writing is a business, and most readers read a lot. For me, seven years of prep was too long. I knew I had to find a way to speed it up if I wanted to be a published author with more than one book credit. I write cozy mysteries, and they’re generally between 71 and 75k words. I write a series, so I try to think about the next book, and I also make sure to mention something that happened in a previous book to remind readers of past adventures or to peak their interest if they haven’t read the earlier books. Getting Started - I spend about 2-3 weeks doing a summary outline for each book. This helps me see plot holes. It helps me know where to add clues and red herrings. It also lets me plan out the murder or caper. I know who does it and why. It also keeps me from getting stuck in the saggy middle of the writing process. I know what goes in each chapter. This summary also helps me write the dreaded synopsis later. It is the plan or roadmap when I have to pick up the project on different days. The Outline - When it’s done, I look over each chapter to make sure there’s enough suspense. Sometimes as writers, we want to move on to the next thing, but you need to slow down the action to build tension. I also highlight the comic events and the romance to make sure they’re sprinkled throughout the story. I also check to make sure there are enough motives for some of the other characters, so it might be plausible that they are the guilty party. The Characters - I have a spreadsheet for each book in the series. It has a column for each book. I list basic facts for each person to make sure I keep important attributes consistent. Examples include what kind of car they drive, personality traits, hair color, eye color, etc. I also have a second chart to list key places in the book. The First Draft - When I sit down to create the first draft, I just write. I don’t go back and edit and revise. I just write. This is what the great Mary Burton calls the “sloppy copy.” During the writing time, I set a word count goal to keep me on target. I usually do 1k on days I have to work and 3k on weekends and holidays. If I stick to my schedule, I can usually have a rough, first draft in a little over two months. Life does get in the way sometimes. When that happens, I try to write ahead of my word count goal. If I can’t plan ahead, I don’t beat myself up over it. I also don’t stop to research or verify things while I’m writing. I make a note in the manuscript and highlight it. That way, I know to go back and check on it during revisions. Keep writing. Time for Revisions - When I finish the first draft, I let it sit for a couple of days. Then I jump into revision and editing mode. I usually do three or four full revisions on the entire book. I print it out and proofread on paper. I run spell check each time there is a round of revision to catch any little typo gremlins that found their way into the story. Beta Readers and Critique Group - When I think I’m done with the revisions, I let critique or beta readers give it a whirl, and they always provide good feedback. When I get their suggestions back, I do more revisions and proofreading. Editors - I am so fortunate to have a fabulous agent and great editors, so I don’t pay for an independent editor anymore. But before I had these amazing resources, I did hire an editor to go through my manuscript. You often get one chance to pitch to an agent or publisher, and I had to make my work the best it could be. Each round of editing leads to more revisions and proofreading. (Spoiler alert: When the publisher gets the manuscript, there are several more rounds of revisions and proofs to check.) The Agony of Deadlines - One book in each of my three cozy series comes out each year. I don’t write well under a lot of pressure, especially of a looming deadline. I try to write ahead of my deadlines, so I have time for the hours of revisions ahead of my contract deadlines. Flexibility and Grace - I create my outlines and daily word counts as tools to keep me on track. If I need to add or remove a chapter to make the book better, I just make a note on the outline and write on. And if I don’t make my word count one day, it’s not the end of the world. Life happens. I try to get back on track during the next writing session. This is what I’ve found works for me. Try pieces and parts that appeal to you but know that your style is your own. If something doesn’t work, try another technique. Through the years, Heather Weidner has been a cop’s kid, technical writer, editor, college professor, software tester, and IT manager. She writes the Delanie Fitzgerald Mysteries, The Jules Keene Glamping Mysteries, and The Mermaid Bay Christmas Shoppe Mysteries.She is a member of Sisters in Crime – Central Virginia, Sisters in Crime – Chessie, Guppies, International Thriller Writers, and James River Writers. Originally from Virginia Beach, Heather has been a mystery fan since Scooby-Doo and Nancy Drew. She lives in Central Virginia with her husband and a pair of Jack Russell terriers. by Erik S. Meyers As I write this, I still can't believe my first cozy crime just published this December. I love mysteries and always wanted to write one myself. At the beginning of the pandemic, I had a lot of time on my hands, as many people did. So I got to writing. Three and a half years later, Death in the Ozarks will be published by Level Best Books December 12. So how did I get here? My writing journey began with a novel idea way back in March 2000. That book became my Jewish LGBTQ historical fiction novel Caged Time I self-published with Mirador Publishing in February 2021. From my research, I realized to get a literary agent and a publisher could be a bit easier if I already had something published, even self-published. In June 2020, I self-published my business book, The Accidental Change Agent, a curated series of essays on a wide range of topics from communications, digital transformation, living abroad and more. As the pandemic began, I sat down to write a murder mystery/cozy crime. I love reading mysteries and always wanted to my hand at my own. I did outline the basic story and the characters before I began writing. In a cozy crime, it is important to be clear on who could be the murderer and why and where before you begin. I sketched out several scenarios as I wasn't quite sure. But I also used the ideas to sprinkle clues throughout the book. The mark of a good mystery is allowing the reader to help solve the crime. You shouldn't hide key details or clues from them, in my opinion. I was astounded that I finished the first draft in about 3 months. The writing just flowed, which it doesn't always. So what next? I reworked it myself but I believe it is essential to have an outside editor. You are too close to your writing. I found a great editor through Reedsy and she helped me rework the story dramatically. That's another important thing about writing. Your goal is to tell a great story, not cling to every word in the first draft. You won't be successful. Believe me, I know! The editing and rework took some time, but by the beginning of 2021 I felt I was ready to try and pitch Death in the Ozarks to literary agents and small publishers. I kept an extensive spreadsheet of people I had contacted once I started querying April 2021. In total I contacted 66 publishers or agents. I was so lucky to find my wonderful literary agent Cindy Bullard at Birch Literary. Finding her was really a quirk: it was through PitMad on Twitter (now X). Writers pitch with hashtags and agents and publishers like posts that they want to find out more about. She has been such a strong supporter and was able to sell Death in the Ozarks to Level Best Books (in a three-book deal) in May 2022 and to Blackstone Audio for the audio version in July 2022. The best advice I can give to someone is: don't give up! One rejection is not the end of the world. And remember, not everyone likes everything they read, so why should an agent or publisher. Keep going, trust in yourself and your writing, and you will go far. Be well! Currently in Austria, Erik S. Meyers is an American abroad for years and years who has lived or worked in six countries on three continents, the longest in Germany. He is an award-winning author and communications professional with over 25 years of expertise in a variety of corporate roles. Reading and writing are his passions, when he is not hiking one of the amazing trails in Austria or elsewhere.

by Charles Philipp Martin  I do not know you. But if you’re attempting to write a novel in 30 days, I know a couple of things about you. One is, you’re insane. The other is you love books, writing, and words. And for this I think you’re a good person, and worth a bit of my time. But I won’t kid you. What you’re trying to do is very difficult. Especially if you want to create something good. Perhaps these few hints of mine will help.

Sure, it’s a big responsibility. But if you’re not up to it, the porta potties are filling up fast.  Charles Philipp Martin grew up in New York City's Greenwich Village. His father was an opera conductor and both his parents well-known opera translators and librettists who never uttered the word "parenting" but knew enough to steep their family in music and literature. After attending Columbia University and Manhattan School of Music, Martin took off for a six-year paid vacation in the Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra. While in Hong Kong he hung up his bow and turned to writing, spending four years as a Sunday Magazine columnist for the South China Morning Post, and writing for magazines all over Southeast Asia. His weekly jazz radio show 3 O'Clock Jump was heard every Saturday on Hong Kong’s Radio 3 for some two decades. Neon Panic, his first novel featuring Hong Kong policeman Inspector Herman Lok, was published in 2011. The second Inspector Lok novel, Rented Grave, will be coming out from Level Best Books in the summer of 2024. Martin now lives in Seattle with his wife Catherine. Photo: Lincoln Potter By Heather Weidner  Writing is a business. You, as a writer, need to treat your work that way. Also, writers need to understand that publishing is a business. Book stores get hundreds of requests for signings. They have to outlay time and money for events for staffing, stocking books, and promotion. Many are choosy or reluctant to host unknown authors. Some will not host authors whose unsold books are not returnable. Find ways to sell your proposed signing (e.g. book talk on a subject that their shoppers would be interested in, providing a group of authors who can bring readers to the store, a marketing campaign for publicizing the event). Find out if they will let you provide the books on consignment. Agents, editors, and publishers sign authors that they think they can sell their work. Sometimes, it’s not your writing. It could be that the topic/subject has been done before, and it will be hard to sell in your genre. Do your research of what is out there before you write the next bookshop or knitting mystery. Publishers are looking several years ahead to fill their slots, and there are not a lot of openings on the dockets. It takes months/years sometimes for a book to be published traditionally. Make your manuscript the best it can be before you start querying. Always be professional. It sounds like a no-brainer, but you want to be easy to work with. People tend to avoid the whiners, divas, and complainers. Make sure that you are polished and that your marketing materials look professional.

Writing is a tough business. Everyone has feedback, and there are a lot of rejections. But there are things you can do to be prepared. Professionalism is key. Through the years, Heather Weidner has been a cop’s kid, technical writer, editor, college professor, software tester, and IT manager. She writes the Delanie Fitzgerald Mysteries, The Jules Keene Glamping Mysteries, and The Mermaid Bay Christmas Shoppe Mysteries.She is a member of Sisters in Crime – Central Virginia, Sisters in Crime – Chessie, Guppies, International Thriller Writers, and James River Writers.

Originally from Virginia Beach, Heather has been a mystery fan since Scooby-Doo and Nancy Drew. She lives in Central Virginia with her husband and a pair of Jack Russell terriers. by Alan Orloff Writer’s Block. Such ugly words. Funny how the mere mention of it strikes terror into the hearts of writers. I have to say, I don’t really believe in writer’s block. Get in the chair, turn on your computer, and start typing. Plumbers don’t get plumber’s block, do they? (At least I don’t think they do…)

Anyway, there certainly are times when the words don’t seem to flow very well. And sometimes, even when the words are appearing on your computer screen, they seem dull and lifeless. How do you get past “stuck?” Try these tips: Work on a different section of your manuscript. Jump to the end, or skip to a scene where you know exactly what’s going to happen. The words might flow more freely. Do something else. Stop banging your head against the wall and trust your subconscious to sneak up on the problem from a different angle. Watch TV, go to the movies, lace up your jogging shoes and get some exercise. If you’re looking for something a little more torturous, clean your house. After an hour of scrubbing floors, I’m ready to get back to writing. Re-read some of your other work. Pull out some polished examples of your writing and give them another read. You did it once, you can do it again. Read someone else’s work. Find a book by an author you admire. Read it to absorb the flow and energy of something you connect with. Type another author’s work. If just reading a book isn't enough, try typing a few pages of someone else’s work, just to get the creative juices flowing. When you’re done, be sure to delete it all. I’m not coming to visit you in prison. Write something in a different genre. If you are a crime writer, try writing something that’s humorous or autobiographical or features talking goldfish. Write in a different style or voice. Switch from first person to third (or vice versa) to shake things up. Note: Never attempt to write in second person. That’s just weird. Write in a different form. If you write prose, try poetry. If you write novels, try a short story (or a cell phone novel). Or log some serious time on Twitter. Read a book on writing. Stephen King's On Writing or Anne Lamott's Bird by Bird are a couple of my favorites. Mix up your routine. Try listening to music (or a different kind of music) or try writing at a different time of day than usual. Try varying your locations, too. A park, coffeehouse, or deserted alley may get those juices flowing (especially a deserted alley at night!). Bribe your muse. Promise your muse you'll do something nice for him/her after you get a few scenes written. Lunch with a friend, a round of golf, or a box of chocolates have been known to work. (So I've heard.) If these don’t work, I have one more suggestion. Tell yourself that you’re on a tight deadline and your draft is due tomorrow. That’ll get you writing. (So I’ve heard.) ************** Alan Orloff has published ten novels and more than forty-five short stories. His work has won an Anthony, an Agatha, a Derringer, and two ITW Thriller Awards. His latest novel is SANCTUARY MOTEL, from Level Best Books. He loves cake and arugula, but not together. Never together. He lives and writes in South Florida, where the examples of hijinks are endless. www.alanorloff.com By Marlie Parker Wasserman How do authors select the names of their characters? Some look to lists of popular names. Some hold contests among their fans. Some try to emulate Charles Dickens by selecting names that describe their characters. Readers may assume that writers of historical fiction have an easier time because they pluck their characters’ names from the historical record. Not always.

For my first historical novel, The Murderess Must Die, I established a guiding principle that I continue to use—or I should write aim to use—as I write historical fiction. When a fact is known, I stick to it. When a fact is unknown, I invent. To figure out the known, I research for months, then I start writing. For that first novel, only well into my writing did I realize I had naming problems. Many of my characters, the real people who are part of the story, had the same names, or confusing names. If I could barely keep the characters straight, how could readers? In finishing my third novel, I’ve come to sort my naming problems into two categories: characters in the historical record who have the same name, usually common names for the Gilded Age and the Progressive Age, and characters with names too common to research. Let me start with the second category, which always produces chuckles. For my newest novel, Inferno on Fifth, I needed to research New York City’s Buildings Commissioner in 1899, a real person named Thomas Brady. Googling him turns up thousands of useless leads to a football player. I’ve also had to research Alfred Pope, an industrialist from Cleveland. I cannot google his full name successfully because newspapers reporters often didn’t know it. During the week that Mr. Pope figures in my novel, American newspapers reported on the serious illness of Pope Leo XIII. You can imagine the results from googling Pope. The more common problem I face is common names. They drive me crazy. Were all men who lived around the year 1900 named William or Frank? Two policemen who witnessed the crime scene at the center of my first novel had the name William Maher. I had to give one a nickname. In my second novel, Path of Peril, set in Panama in 1906, I encountered two historical figures with similar names—Elliott Roosevelt, brother of Teddy, and R.B. Elliott, a little-known labor leader. I chose to minimize the role of the labor leader. I encountered two James—valet James Amos and secret service agent James Sloan. I opted to call the valet by his last name. In writing my third novel, Inferno on Fifth, women’s names become the issue. Two women named Ida figure in my story—Ida McClusky, sister of a detective, and Ida McKinley, wife of a president. I chose to refer to the former as, simply, the sister. I also manipulate three Helens. I allow only Helen Gould, the daughter of Jay Gould, to keep her name. And I grapple with two Alices, a mother and daughter. I’m still pondering how to keep them straight for the reader. Even less common names cause problems. For The Murderess Must Die, I researched details about the brother of my primary character, a young man with the seemingly distinctive name of Garrett Terhune Garretson, who fought in the Civil War. I found two men with the exact same name, living at about the same time. I spent weeks going down rabbit holes with the wrong man. With that book I also encountered a problem with nicknames. I thought Penelope, my primary character’s mother, was nicknamed Ellen, then it appeared that whether that was right or not, another Ellen was my character’s sister. In each of my novels I erase the correct names of some of my characters for, as the phrase goes, the good of the story. I choose readability over accuracy. Sadly, and cowardly, I let my more well-known characters keep their names as I weigh how likely readers are to notice errors. In every case, I provide explanations and apologies in my author’s notes. I want to offer a call for action at the end of this little essay—please, parents, chose distinctive names for your children or we will have generations of novelists trying to sort out Rachels, Emmas, Noahs, and Olivers. ********** Marlie Parker Wasserman writes historical crime fiction. Her previous books are The Murderess Must Die and Path of Peril. Her latest book, Inferno on Fifth, is inspired by the true story of the shocking fire that leveled one of Manhattan’s elegant hotels twelve years before the infamous Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire. When not writing, Marlie travels throughout the world and tries to remember how to sketch. She lives with her husband in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. By Jason Monaghan One challenge of writing a thriller set in a historic period is that we know what happened. Even if most of your readers are not history experts, they will be aware of the big picture and can quickly dive into Wikipedia to flesh out the facts. We know which US Presidents were assassinated, who won WW2 and are sure the Titanic sank. A reader can anticipate what is going to happen.

Even if we know our history, tension can be created against a historic backdrop that is fixed, for example in the Phillip Kerr books set in 1930s and 1940s Germany. Innumerable crimes and misdemeanours and cunning plots can be fitted into this ‘Golden Age’ with only passing nods to the historic timeline. Much happened that is not in the history books. Even if writing a thriller faithful to a well-known event such as Robert Harris’ Munich a great deal of the dialogue, plot and behind-the-scenes action needs to be made up. Crucially, although modern readers know how it all turned out, the characters don’t. The writer needs to convey their hopes and fears and plans when the future is unknown. To them the end is not inevitable, and even the historic outcome need not pre-determine their fate as individuals. Characters should not be granted too much foreknowledge and so take actions that in hindsight we know are mistakes; they may invest in the stock market in 1928 because it seemed like a good idea at the time. Even if the reader is not surprised by the outcome of events, they are rewarded by how the protagonists react. Historic thriller plots are made easier if the lead characters are minor players in the great game; a soldier not a general, a highwayman not a king. Major historical figures are given only walk-on parts, perhaps spouting lines they actually used. Only a little license is needed for our hero to be one of Columbus’ crewman or a Lady-in-waiting to Anne Boleyn. Take a little more license and one of our characters can play a pivotal role, such as being one of the senators who sticks a dagger into Julius Caesar. Writing alternative history such as Phillip K Dick’s The Man in the High Castle is a bolder step still. It opens up possibilities but requires a suspension of disbelief by the reader. The altered timeline needs to be explained and the bigger the departure from reality, the more thought the writer must put into world-building. Fantastic elements need to be minimised so that once over the initial hurdle everything about this changed world feels logical. The more recognisable elements of the real historic period that are included, the less of a jump it will be for the reader. The history is ‘wrong’, but it should feel plausible. We are not writing history books so much of the research that underpins a thriller must be set aside, keeping only the nuggets that add richness to the story and provide the context. However, some facts can prove to be inconvenient and box the plot in if not derailing it entirely. Changing just a few of those inconvenient facts raises the reader’s doubts whether we will see history unfold as it should. Perhaps Hitler will be assassinated by our hero, or perhaps JFK will be saved. The character’s uncertainty about what could happen becomes more real if the reader also becomes uncertain. It’s a thriller, and we expect the unexpected. **************** Jason Monaghan is an author and archaeologist. Blackshirt Masquerade by is set in 1935 in a Britain under the rising threat of fascism. The fascist bid for power accelerates during the ‘Abdication Crisis’ of 1936 in Blackshirt Conspiracy. Both are published by the Historia Imprint of Level Best Books. By Erica Miner When it comes to old adages, “Write what you know” ranks right up there with, “Practice makes perfect” and, “Have no fear of perfection, you'll never reach it.”

In a recent webinar, Level Best Books author James L’Etoile discussed how our writers’ life experiences influence what we write. His background of many years working in the criminal justice system infuses his murder mysteries with compelling authenticity. I am able to relate to that concept, as my own life experiences have proved to be a goldmine of material for my fiction. My 21 years as a violinist with New York’s Metropolitan Opera have provided a sharp-edged realism to my Julia Kogan “Opera Mystery” series. The first in the series, Aria for Murder, takes place at the Met. My protagonist, Julia Kogan, is a direct clone of myself when I first started out at the company: a gifted young violinist debuting with the Met Opera Orchestra, trying to make her way in a difficult, demanding profession that is in many ways still dominated by men. The people Julia encounters—fellow musicians, conductors, chorus members, stagehands, stage managers and the like—populate this story as reflections of my own relationships with company members. The real-world personality traits of people who were an integral part of my daily life at this home-away-from-home that was the Met Opera formed the basis of many of the characters I created in Aria for Murder. But I also witnessed actual situations that initially inspired me to write this series: a number of nefarious goings-on that sparked my imagination and caused me to embroider and escalate the possibilities of these circumstances into behind-the-scenes murder and intrigue at this venerable institution. Writing this story also gave me a unique opportunity to kill off the people who made my life miserable! (Not all of them…I had to save a few for the sequels, which will thrust Julia into heaps of trouble at different opera houses across the country.) The Met Opera is a unique world: the most prestigious opera company on the planet, where superstars like Caruso, Pavarotti and Domingo have been entertaining the cream-of-the-crop of opera aficionados for centuries. Standards are the highest on the planet; so are the stakes. These elite audiences, however, have no idea what goes on behind all the glamour and glitz. Ultimately, revealing the dark side of the opera world is my rationale for creating these operatic whodunits. Under those crystal chandeliers, behind that “Golden Curtain,” hundreds of people are working in different jobs simultaneously, and always at odds with each other: opera superstars, comprimarios (lesser solo singers), directors, conductors, orchestra, chorus, ballet, stagehands, wardrobe, make up, wigmakers and more. Egos clash, tempers flare. There’s no love lost between any of them. Take the orchestra, for example: 100 neurotic musicians thrown together in a hole in the ground with no air and no light, 7 days a week, days, nights, weekends. You see more of these people than your own families. Sooner or later, someone’s going to want to kill somebody. Aria for Murder. In Julia, however, I have created a protagonist who, unlike myself, is capable of rising above her fears to plunge herself into a murder investigation. I could never be that brave. That is where the beauty of writing fiction can transform “Write what you know” into “Create a character who is the kind of person you’d like to be.” And what could be better than that? ### Former Metropolitan Opera violinist Erica Miner is an award-wining author, screenwriter, arts journalist, and lecturer. Her debut novel, Travels with my Lovers, won the Fiction Prize in the Direct from the Author Book Awards, and her screenplays have won awards in the WinFemme, Santa Fe and Writers Digest competitions. Based in the Pacific Northwest, Erica continues to balance her reviews and interviews of real-world musical artists with her fanciful plot fabrications that reveal the dark side of the fascinating world of opera. Aria for Murder, published by Level Best in Oct. 2022, is the first in her Julia Kogan Opera Mystery series. Prelude to Murder, the sequel set at the Sante Fe Opera, was released September 2023. Book three,taking place at the San Francisco Opera is due for release in 2024. https://www.ericaminer.com By Katherine Ramsland Most of us enjoy a sense of the familiar. It’s predictable, comforting, and often preferable, even if lacking in thrill. It allows us to relax and gather ourselves. That’s why adding consistent rituals throughout your series can deepen your readers’ connection to your characters. They experience repeated rituals as an element of series consistency.

When I planned my “Nut Cracker Investigations” for Level Best Books, I wanted to develop ways to cohere my PI team. I have three primary and several secondary members, but I wanted the primaries to participate most clearly in closure and commitment. All for one, and one for all, that type of thing. Annie Hunter, a forensic psychologist, manages the investigation agency; Ayden Scott is her PI, and Natra Gawani her data manager and confidante. My secondary team features a digital expert, a forensic meteorologist, and an attorney. They’re in and out as needed. One ritual I use runs in the background: Annie likes red wine, so whenever the team has an opportunity to brainstorm over wine, they pick a label that matches the situation. Stormy Weather during a tornado, for example. Readers recognize this display of character (and sometimes they buy wine for book club signings). A more important ritual is the case debriefing. Although there are plenty of times when the team brainstorms, it’s the post-case gathering that really unites them. No one else is allowed, no matter what part they might have played. This is a solemn Nut Crackers ritual. Here, they patch holes, lick wounds, plan improvements, and show how much the work means to them. They might tease or toast each other, or even mourn together. For them, it’s the best part of the case. I include a debrief scene in every novel because I want readers to expect it, appreciate it, and watch how Annie responds to their own lingering questions. She might even use the time to set up the next case, whetting readers’ appetites. Like Annie’s wine, rituals pair well with our sense of anticipation and connection. Here are three psychological reasons to develop some rituals for your series:

It’s worth considering rituals that put your characters in motion or reveal their qualities. Thus, you’ll get an added benefit, and readers will likely look forward to how these rituals play out. ___ Katherine Ramsland has played chess with serial killers, dug up the dead, worked with profilers, and camped out in haunted crime scenes. As a professor of forensic psychology and a death investigation consultant, she seeks unique angles. The author of 71 books, she’s been a forensic consultant for CSI, Bones and The Alienist and an executive producer on Murder House Flip and A&E’s Confession of a Serial Killer. She’s become a go-to expert for the most deviant forms of criminal behavior, which provides background for her Nut Cracker Investigations. Her second novel in the serial, In the Damage Path, is now available. |

Level Best AuthorsMusings from our Amazing Group of Authors Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Level Best Books18100 Windsor Hill Rd

Olney MD 20832 |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed