|

By Kathleen Marple Kalb “Marriage is a rotten deal for a woman.”

When Ella Shane says this to Gilbert Saint Aubyn, Duke of Leith, soon after they meet in the spring of 1899, she’s not flirting or exaggerating; she’s just stating a simple fact of 19th century life, at least from her point of view. She’s also giving the main reason it takes her three books, several murders, and a brush with death to decide to marry the Duke. (The wedding FINALLY comes in A FATAL RECEPTION, this April!) Marriage seems like prison to Ella, an Irish-Jewish Lower East Side orphan who’s clawed out an independent life and career as an opera singer specializing in “trouser,” male soprano, roles. It was certainly the end of legal freedom for most women at the time. Even in the late 19th century, when a woman married, she essentially ceased to exist as an independent person. The legal doctrine was called “femme couvert,” literally translated as “covered woman,” meaning the woman’s rights were covered by her husband’s power. You can see how that could lead to all sorts of trouble. All of a woman’s money and property, not to mention her person – and her children – were effectively under her husband’s control. She could earn money, but he decided how it was spent. She would bear the children and raise them, but they, too, were his property. Laws were starting to address the idea that married women might inherit or earn property of their own, but on the ground, men still had close to absolute power over their wives. By the late 1800s and early 1900s, divorce was just barely possible in particularly egregious cases of abuse or financial neglect – and men could ditch an unfaithful wife. But a woman could not expect to take her children with her if she left a bad marriage, even a horrifically abusive one. In less extreme cases, women just had to put up with the daily knowledge they weren’t real people in the eyes of the law, with little or none of the power a man had. A woman could do almost nothing without her husband’s consent – and that didn’t change for decades. There are plenty of women alive and well today who remember having to ask their husbands to co-sign on their credit cards. Women like Ella, single and making a living on her own, were rare at the time, but not unknown. Often, they lived with parents or family, as Ella does with her cousin Tommy, and often (based on advice writing and fiction of the time) the families vexed about having an independent woman around, and what to do with her. Until the late 19th century, a woman alone with money was usually a widow, and people knew how to handle that. She was taking care of her late husband’s estate for the benefit of her children and needed some legal and social room for the purpose. A single woman? Who knows what she might do? The one thing she certainly could do, though, is run her own affairs without anything more than advice from a man. Ella is well aware of that fact, and while she’s glad to have Tommy as friend, protector, and manager, she also prizes her independence. Independence she would have to unconditionally surrender in a match with any man, even a worthy one who is her equal. Maybe especially with a worthy man. If a clerk expects his wife to stop working and tend to his home, how much more would a powerful and well-off man expect? The answer, of course, is everything. Women with careers, whether on the stage or elsewhere, generally gave them up when they married. Ella has no interest in becoming a bird in a gilded cage. All of this is in the room when the Duke makes his reply to Ella’s comment: “Depends on who’s setting the terms.” The terms are what makes all the difference, and why Ella and Gil are now heading to the altar in A FATAL RECEPTION. After more than a year of negotiating their relationship and their future and finally coming to the conclusion that they can’t live without each other, the two have agreed on a marriage contract. It sounds a little cold for a couple madly in love, but it’s the only way for Ella to keep her freedom – and for Gil to show his respect for it. Marriage contracts had always been a part of aristocratic unions, but the diva and her duke make an unusual deal, keeping their property separate and giving her control over her career. Gil surrenders some of what might be his rights in the eyes of the law out of love and respect. As A FATAL RECEPTION opens, the couple has finally settled the property and legal matters, and now they’re navigating something almost as difficult: the transition from courting couple to spouses. While, of course, solving a crime or two. And it’s fair to say both are sure they’re getting a good deal. Kathleen Marple Kalb likes to describe herself as an Author/Anchor/Mom…not in that order. An award-winning radio journalist, she currently anchors on the weekend morning show at New York's #1 news station, 1010 WINS. She’s the author of several mysteries, historical and contemporary. Her short stories appear in anthologies and online and have been short-listed for Derringer and Black Orchid Novella Awards. She grew up in front of a microphone and a keyboard, working as an overnight DJ as a teenager in her hometown of Brookville, Pennsylvania…and writing her first (thankfully unpublished) novel at sixteen. When her son started kindergarten, she returned to fiction, and after two failed projects, some 200 rejections, and a family health crisis, found an agent for the third book – leading to a pandemic debut. In hopes of sharing what she’s learned the hard way, she’s active in writers’ groups including Sisters in Crime and the Short Mystery Fiction Society and keeps a weekly writing survival-tips blog. She, her husband, and their son live in Connecticut, in a house owned by their cat.

1 Comment

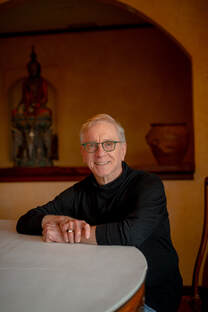

By Bryan E. Robinson, Ph.D. When it comes to your inner critic, my advice is to not take advice from someone who doesn’t like you. That’s like returning to the perpetrator for healing after you’ve been abused. —Patrick Califia, writer

Do you hear voices in your head? Of course you do if you’re a writer. Creative people have one relentless voice, in particular, that lives in our heads and never rests—an inner critic that puts us under the microscope, bludgeons us with criticism, and tells us how worthless, selfish, dumb, or inept we are. That kick-butt voice pops up like burnt toast with such lightning speed we don’t even notice, eviscerating us with name-calling, discouragement, and putdowns. The critical voice tells you that you can’t; you should, ought to, have to, or must. It knows where you live and where to find you. And it does. When you’re working on an important deadline, it stalks you to your desk and whispers over your shoulder as you pen a manuscript. It could be scolding you right now. Listen closely. Do you hear it: “No, that’s not right! You don’t know what you’re doing! You might as well give up! Who do you think you are? You’re an imposter.” Burnt toast anyone? The critical voice in our head isn’t who we are. It’s a part of us, not all of us. It’s the lowercase “self.” Who are we, then? We are the captain of our ship—not a passenger, the coach of our team—not a player, the conductor of our symphony—not a musician, the CEO of our boardroom—not a stakeholder. We’re the true writer’s Self with a capital “S”—the writer who hears and sees the lowercase “self” or critic. There’s no use fighting, debating, or arguing with your inner critic. It always has a comeback and always wins, plus you can’t get rid of it. The key is to watch it and let it come and go without personalizing it. When we oppose or try to reason with the Critic, we give it credence and, instead of streaming on through, it takes up residence. Studies show when the critic comes down hard on ourselves after a mistake or failure, it reduces our creativity and chances of writing success. When you think about it, eviscerating ourselves after a letdown is like fighting the fire department when our house is on fire. It’s just as easy to affirm ourselves with positive messages as it is to tear ourselves down with negative ones. The best way to address the inner critic when it pops up is to observe it like you would inspect a blemish on your hand instead of reacting to it. Listen to it with a dispassionate ear as a part of you. Imagine someone scolding you over your cell phone and you hold the phone away from your ear. In the same way, you can listen to the Critic’s message from afar as a separate part from you, not all of you. In addition to hearing it as a part of you, not you, a dispassionate ear gives you distance from the Critic’s voice and keeps you from attacking yourself. Plus, it keeps you from believing the voice’s made-up story. If you’re stuck with your writing, try replacing criticism with Self-compassion (from the capital Self) each step of the way. Self-compassion is a powerful resilient tool that stands up to harm and is more likely to lead to heights of literary success. So put down your gavel and amp up your kinder, compassionate side. In times of writing struggles, give yourself pep talks, positive affirmations, and talk yourself off the ledge instead of letting your Critic encourage you to jump. Vincent Van Gogh once said, “If you hear a voice within you say, ‘You cannot paint,’ then by all means paint, and that voice will be silenced.” Bryan Robinson says, “If you hear a voice within you say, “You cannot write,” then by all means write, and that voice will be silenced.” Bryan E. Robinson is a licensed psychotherapist and author of 40 nonfiction books. He is also author of two murder mysteries—both soon to come from Level Best Books: Way DEAD Upon the Suwannee River and She’ll Be KILLING Round the Mountain. His tagline is, “I heal by day and kill by night.” He is also author of Daily Writing Resilience: 365 Meditations & Inspirations for Writers. His website is www.bryanrobinsonphd.com. |

Level Best AuthorsMusings from our Amazing Group of Authors Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Level Best Books18100 Windsor Hill Rd

Olney MD 20832 |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed